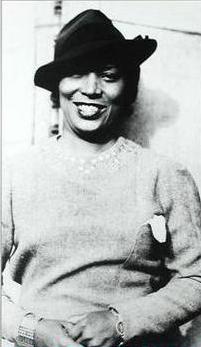

Zora Neale Hurston–Still Watching God (Excerpts From One Of The Greatest Literary Writers Of All Time)

Their Eyes Were Watching God, Excerpt

Ships at a distance have every man’s wish on board. For some they come in with the tide. For others they sail forever on the horizon, never out of sight, never landing until the Watcher turns his eyes away in resignation, his dreams mocked to death by Time. That is the life of men.

Now, women forget all those things they don’t want to remember, and remember everything they don’t want to forget. The dream is the truth. Then they act and do things accordingly.

So the beginning of this was a woman and she had come back from burying the dead. Not the dead of sick and ailing with friendsat the pillow and the feet. She had come back from the sodden and the bloated; the sudden dead, their eyes flung wide open in judgment.

The people all saw her come because it was sundown. The sun was gone, but he had left his footprints in the sky. It was the time for sitting on porches beside the road. It was the time to hearthings and talk. These sitters had been tongueless, earless, eyeless conveniences all day long. Mules and other brutes had occupied their skins. But now, the sun and the bossman were gone, so the skins felt powerful and human. They became lords of sounds and lesser things. They passed nations through their mouths. They sat in judgment.

Seeing the woman as she was made them remember the envy they had stored up from other times. So they chewed up the back parts of their minds and swallowed with relish. They made burning statements with questions, and killing tools out of laughs. It was mass cruelty. A mood come alive. Words walking without masters; walking altogether like harmony in a song.

“What she doin’ coming back here in dem overhalls? Can’t she find no dress to put on? – Where’s dat blue satin dress she left here in? – Where all dat money her husband took and died and left her? – What dat ole forty year ole ‘oman doin’ wid her hair swingin’ down her back lak some young gal? – Where she left dat young lad of a boy she went off here wid? – Thought she was going to marry? – Where he left her? – What he done wid all her money? – Betcha he off wid some gal so young she ain’t even got no hairs- why she don’t stay in her class?”

When she got to where they were she turned her face on the bander log and spoke. They scrambled a noisy ”good evenin’ ” and left their mouths setting open and their ears full of hope. Her speech was pleasant enough, but she kept walking straight on to her gate. The porch couldn’t talk for looking.

The men noticed her firm buttocks like she had grape fruits in her hip pockets; the great rope of black hair swinging to her waist and unraveling in the wind like a plume; then her pugnacious breasts trying to bore holes in her shirt. They, the men, were saving with the mind what they lost with the eye. The women took the faded shirt and muddy overalls and laid them away for remembrance. It was a weapon against her strength and if it turned out of no significance, still it was a hope that she might fall to their level some day.

But nobody moved, nobody spoke, nobody even thought to swallow spit until after her gate slammed behind her. Pearl Stone opened her mouth and laughed real hard because she didn’t know what else to do. She fell all over Mrs. Sumpkins while she laughed. Mrs. Sumpkins snorted violently and sucked her teeth.

“Humph! Y’all let her worry yuh. You ain’t like me. Ah ain’t got her to study ’bout. If she ain’t got manners enough to stop and let folks know how she been makin’ out, let her g’wan!”

“She ain’t even worth talkin’ after,” Lulu Moss drawled through her nose. “She sits high, but she looks low. Dat’s what Ah say ’bout dese ole women runnin’ after young boys.”

Pheoby Watson hitched her rocking chair forward before she spoke.”Well, nobody don’t know if it’s anything to tell or not.Me, Ah’m her best friend, and Ah don’t know.”

“Maybe us don’t know into things lak you do, but we all knowhow she went ‘way from here and us sho seen her come back. ‘Tain’tno use in your tryin’ to cloak no ole woman lak Janie Starks, Pheoby, friend or no friend.”

“At dat she ain’t so ole as some of y’all dat’s talking.”

“She’s way past forty to my knowledge, Pheoby.”

”No more’n forty at de outside.”

“She’s ‘way too old for a boy like Tea Cake.”

”Tea Cake ain’t been no boy for some time. He’s round thirty his ownself.”

“Don’t keer what it was, she could stop and say a few words with us. She act like we done done something to her,” Pearl Stone complained. “She de one been doin’ wrong.”

“You mean, you mad ’cause she didn’t stop and tell us all her business. Anyhow, what you ever know her to do so bad as y’all make out? The worst thing Ah ever knowed her to do was taking a few years offa her age and dat ain’t never harmed nobody. Y’all makes me tired. De way you talkin’ you’d think de folks in dis town didn’t do nothin’ in de bed ‘cept praise de Lawd. You have to ‘scuse me, ’cause Ah’m bound to go take her some supper.”Pheoby stood up sharply.

“Don’t mind us,” Lulu smiled, ” just go right ahead, us can mind yo’ house for you till you git back. Mah supper is done. You bettah go see how she feel. You kin let de rest of us know.”

“Lawd,” Pearl agreed, ”Ah done scorched-up dat lil meat and bread too long to talk about. Ah kin stay ‘way from home long as Ah please. Mah husband ain’t fussy.”

“Oh, er, Pheoby, if youse ready to go, Ah could walk over dere wid you,” Mrs. Sumpkins volunteered. “It’s sort of duskin’ down dark. De booger man might ketch yuh.”

“Naw, Ah thank yuh. Nothin’ couldn’t ketch me dese few steps Ah’m goin’. Anyhow mah husband tell me say no first class booger would have me. If she got anything to tell yuh you’ll hear it.”

Pheoby hurried on off with a covered bowl in her hands. She left the porch pelting her back with unasked questions. They hoped the answers were cruel and strange. When she arrived at the place, Pheoby Watson didn’t go in by the front gate and down the palm walk to the front door. She walked around the fence corner and went in the intimate gate with her heaping plate of mulatto rice. Janie must be round that side.

She found her sitting on the steps of the back porch with the lamps all filled and the chimneys cleaned. “Hello, Janie, how you comin’?”

“Aw, pretty good, Ah’m tryin’ to soak some uh de tiredness and de dirt outa mah feet.” She laughed a little.

“Ah see you is. Gal, you sho looks good. You looks like youse yo’ own daughter.” They both laughed. “Even wid dem overhalls on, you shows yo’ womanhood.”

“G’wan! G’wan! You must think Ah brought yuh somethin’. WhenA h ain’t brought home a thing but mahself.” “Dat’s a gracious plenty. Yo’ friends wouldn’t want nothin’ better.”

“Ah takes dat flattery offa you, Pheoby, ’cause Ah know it’s from de heart.” Janie extended her hand. ”Good Lawd Pheoby! ain’t you never goin’ tuh gimme dat lil rations you brought me? Ah ain’t had a thing on mah stomach today exceptin’ mah hand. “They both laughed easily. “Give it here and have a seat.”

“Ah knowed you’d be hongry. No time to be huntin’ stove wood after dark. Mah mulatto rice ain’t so good dis time. Not enough bacon grease, but Ah reckon it’ll kill hongry.”

“Ah’ll tell you in a minute,” Janie said, lifting the cover. ”Gal, it’s too good! you switches a mean fanny round in a kitchen.”

“Aw, dat ain’t much to eat, Janie. But Ah’m liable to have something sho nuff good tomorrow, ’cause you done come.”

Janie ate heartily and said nothing. The varicolored cloud dust that the sun had stirred up in the sky was settling by slow degrees.

“Here, Pheoby, take yo’ ole plate. Ah ain’t got a bit of use for a empty dish. Dat grub sho come in handy.” Pheoby laughed at her friend’s rough joke. “Youse just as crazy as you ever was.

“Hand me dat wash-rag on dat chair by you, honey. Lemme scrub mah feet.” She took the cloth and rubbed vigorously. Laughter came to her from the big road.

“Well, Ah see Mouth-Almighty is still sittin’ in de sameplace. And Ah reckon they got me up in they mouth now.” “Yes indeed. You know if you pass some people and don’t speaktuh suit ’em dey got tuh go way back in yo’ life and see whut you ever done. They know mo’ ’bout yuh than you do yo’ self. An envious heart makes a treacherous ear. They done ‘heard’ ’bout you just what they hope done happened.”

“If God don’t think no mo’ ’bout ’em then Ah do, they’s a lost ball in de high grass.”

“Ah hears what they say ’cause they just will collect roundmah porch ’cause it’s on de big road. Mah husband git so sick of ’em sometime he makes ’em all git for home.”

“Sam is right too. They just wearin’ out yo’ sittin’ chairs.”

“Yeah, Sam say most of ’em goes to church so they’ll be sureto rise in Judgment. Dat’s de day dat every secret is s’posed to be made known. They wants to be there and hear it all.”

“Sam is too crazy! You can’t stop laughin’ when youse round him.”

”Uuh hunh. He says he aims to be there hisself so he can find out who stole his corn-cob pipe.”

“Pheoby, dat Sam of your’n just won’t quit! Crazy thing!”

“Most of dese zigaboos is so het up over yo’ business till they liable to hurry theyself to Judgment to find out about you if they don’t soon know. You better make haste and tell ’em ’bout you and Tea Cake gittin’ married, and if he taken all yo’ money and went off wid some young gal, and where at he is now and where at is all yo’ clothes dat you got to come back here in overhalls.”

“Ah don’t mean to bother wid tellin’ ’em nothin’, Pheoby ‘Tain’t worth de trouble. You can tell ’em what Ah say if you wants to. Dat’s just de same as me ’cause mah tongue is in mah friend’s mouf.”

“If you so desire Ah’ll tell ’em what you tell me to tell’em.”

“To start off wid, people like dem wastes up too much time puttin’ they mouf on things they don’t know nothin’ about. Now they got to look into me loving Tea Cake and see whether it was done right or not! They don’t know if life is a mess of corn-meal dumplings, and if love is a bed-quilt!”

“So long as they get a name to gnaw on they don’t care whoseit is, and what about, ‘specially if they can make it sound like evil.”

“If they wants to see and know, why they don’t come kissand be kissed? Ah could then sit down and tell ’em things. Ah been a delegate to de big ‘ssociation of life. Yessuh! De Grand Lodge, de big convention of livin’ is just where Ah been dis year and a half y’all ain’t seen me.”

They sat there in the fresh young darkness close together. Pheoby eager to feel and do through Janie, but hating to show her zest for fear it might be thought mere curiosity. Janie full of that oldest human longing- self revelation. Pheoby held her tongue for a long time, but she couldn’t help moving her feet. So Janie spoke.

“They don’t need to worry about me and my overhalls longas Ah still got nine hundred dollars in de bank. Tea Cake got me into wearing ’em-following behind him. Tea Cake ain’t wasted up no money of mine, and he ain’t left me for no young gal, neither.He give me every consolation in de world. He’d tell ’em so too, if he was here. If he wasn’t gone.”

Pheoby dilated all over with eagerness, “Tea Cake gone?”

“Yeah, Pheoby, Tea Cake is gone. And dat’s de only reason you see me back here – cause Ah ain’t got nothing to make me happy no more where Ah was at. Down in the Everglades there, down on the muck.”

“It’s hard for me to understand what you mean, de way you tell it. And then again Ah’m hard of understandin’ at times.”

”Naw, ’tain’t nothin’ lak you might think. So ’tain’t no usein me telling you somethin’ unless Ah give you de understandin ‘to go ‘long wid it. Unless you see de fur, a mink skin ain’t no different from a coon hide. Looka heah, Pheoby, is Sam waitin’ on you for his supper?”

”It’s all ready and waitin’. If he ain’t got sense enough to eat it, dat’s his hard luck.”

“Well then, we can set right where we is and talk. Ah got the house all opened up to let dis breeze get a little catchin’.

”Pheoby, we been kissin’-friends for twenty years, so Ah depend on you for a good thought. And Ah’m talking to you from dat standpoint.”

Time makes everything old so the kissing, young darkness became a monstropolous old thing while Janie talked.

Negroes Without Self-Pity by Zora Neale Hurston, November 1943 for The American Mercury

I may be wrong, but it seems to me that what happened at a Negro meeting in Florida the other day is important—important not only for Negroes and not only for Florida. I think that it strikes a new, wholesome note in the black man’s relation to his native America.

It was a meeting of the Statewide Negro Defense Committe. C.D.Rogers, President of te Central Life Insurance Company of Tampa, got up and said: “I will answer that question of whether we will be allowed to take part in civic, state and national affairs. the answer is – yes!” Then he explained why and how he had come to take part in the affairs of his city.

“The truth is,” he said, “that I am not always asked. Certainly in the beginning I was not. As a citizen, I saw no reason why I should wait for an invitation to interest myself in things that concerned me just as much as the did other residents of Tampa. I went and I asked what I could do. Knowing that I was interested and willing to do my part, the authorities began to notify me ahead of proposed meetings, and invited me to participate. I see no point in hanging back, and then complaining that I have been excluded from civic affairs.

“I know that citizenship implies duties as well as privileges. It is time that we Negroes learn that you can’t get something for nothing. Negroes, merely by being Negroes, are not exempted from natural laws of existence. If we expect to be treated as citizens, and considered in community affairs, we must come forward as citizens and shoulder our part of the load. The only citizens who count are those who give time, effort and money to the support and growth of the community. Share the burden where you live! ”

And then J. Leonard Lewis, attorney for the Afro-American Life Insurance, had something to say. First he pointed to the growing tension between the races throughout the country. Then he, too, broke tradition. The upper-class Negro, he said, must take the responsibility for the Negro part in these disturbances.

“It is not enough,” he said, “for us to sit by and say ‘We didn’t do it. Those irresponsible, uneducated Negroes bring on all this trouble.’ We must not only do nothing to whip up the passions among them, we must go much further. We must abandon our attitude of aloofness to the less educated. We must get in touch with them and head off these incidents before they happen.

“How can we do that? There is always some man among them who has great prestige with them. He can do what we cannot do, because he is of them and undrstands them. If he says fight, they fight. If he says, ‘Now put away that gun and be quiet,’ they are quiet. We must confer with these people, and cooperate with them to prevent these awful outbreaks that can do no one any good and everybody some harm. Let us give up our attitude of isolation from the less fortunate among us, and do what we can for peace and good-will betwen the races.”

Not anything world-shaking in such speeches, you will say. Yet something profound has happened, of which these speeches are symptoms and proofs. Look back over your shoulder for a minute. Count the years. if you take in the twenty-odd years of intense Abolitionist speaking and writing that preceeded the Civil War, the four war years, the Reconstruction period and recent Negro rights agitations, you have at least a hundred years of indoctrination of the Negro that he is an object of pity. Becoming articulate, this was in him and he said it. “We were brought here against our will. We were held as slaves for two hundred and forty-six years. We are due something from the labor of our ancestors. Look upon us with pity and give!” The whole expression was one of self-pity without a sense of belonging to America and what went on here.

Put that against the statements of Rogers and Lewis, and you get the drama of the meeting. The audience agreed and applauded. Tradition was tossed overboard without a sigh. Dr. J. R. Lee, president of Florida A & M College for Negroes, got up and elaborated upon the statements: “Go forward with the nation. We are citizens and have our duties as such.” Nobody mentioned slavery, Reconstruction, nor anysuch matter. It was a new and strange kind of Negro meeting—without tears of self-pity. It was a sign and symbol of something in the offing.

Mules and Men, Excerpt

Ole John was a slave, you know. And there was Ole Massa and Ole Missy and de two li’ chidren- a girl and a boy.

Well, John was workin’ in de field and he seen de chidlren out on de lake in a boat, just a hollerin”. They had done lost they oars and was ’bout to turn over. So then he went and tole Ole Massa and Ole Missy.

Well, Ole Missy, she hollered and said: “It’s so sad to lose these ’cause Ah ain’t never goin’ to have no more children.” Ole Massa made her hush and they went down to de water and follered de shore on ’round till they found ’em. John pulled off his shoes and hopped in and swum out and got in de boat wid de children and brought ’em to shore.

Well, Massa and John take ’em to de house. So they was all so glad ’cause de children got saved. So Massa told ‘im to make a good crop dat year and fill up de barn, and den when he lay by de crops nex’ year, he was going to set him free.

So John raised so much crop dat year he filled de barn and had to put some of it in de house. So friday come, and Massa said, “Well, de day done come that I said I’d set you free. I hate to do it, but I don’t like to make myself out a lie. I hate to git rid of a good nigger like you.”

So he went in de house and give John one of his old suits of clothes to put on. So John put it on and come in to shake hands and tell ’em goodbye. De children they cry, and Ole Missy she cry. Didn’t want to see John go. So John took his bundle and put it on his stick and hung it crost his shoulder.

Well, Ole John started on down de road. Well, Ole Massa said, “John, de children love yuh.”

“Yassuh.”

“John, I love yuh.”

“Yassah.”

“And Missy like yuh!”

“Yassuh.”

“But ‘member, John, youse a nigger.”

“Yassuh.”

Fur as John could hear ‘im down de road he wuz hollerin’, “John, Oh John! De children loves you. And I love you. De Missy like you.”

John would hollor back, “Yassuh.”

“But ‘member youse a nigger,tho!”

Ole Massa kept callin ‘im and his voice was pitiful. But John kept right on steppin’ to Canada. He answered Ole Massa every time he called ‘im, but he consumed on wid his bag.